Essential Methods for Planning Practitioners

Skills and Techniques for Data Analysis,

Visualization, and Communication

This book assembles and organizes a selected range of methods and techniques that every planning practitioner should know to be successful in the contemporary global urban landscape. The book is unique because it links different aspects of the planning/policy-making enterprise with the appropriate methods and approaches, thus contextualizing the use of specific methods and techniques within a sociopolitical and ethical framework. This volume familiarizes readers with the diverse range of methods, techniques, and skills that must be applied at different scales in dynamic workplace environments where planning policies and programs are developed and implemented. This book is an invaluable resource in helping new entrants to the planning discourse and profession set aside their own disciplinary biases and empowering them to use their expert knowledge to address societal concerns.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 - Planning as Storytelling

-

The world of planning has drastically changed over the past few years. Understanding this change requires to briefly revisit the historic roots of planning and geography. Little has prepared the profession for the brave new data world though where data is confused with information (Cohen 2002, Kerski & Clark 2012). We juxtapose the current situation, where everybody thinks they are planners with traditional planning models and prepare the reader to acknowledge people's experience while defending her expertise. In our conceptualization of planning, this is not a compromise position but a world view. This chapter provides some answers to the questions that are often foremost in practitioners’ minds — Why is any discussion of change so “political”? We argue that practitioners should understand the strengths and limits of planning (from the past) to plan more effectively in the future. In the second half of this chapter, we argue that each planning problem, regardless of whether it is simple or complex, large or small in scale, requires its own set of appropriate tools and recipes and illustrate this by outlining a framework of future planning challenges. In addition to climate change, the future long-term societal challenges we highlight are: changing population characteristics; urbanization and migration; immigration; environmental quality and human health; safety and security. The description of these tools and recipes forms the bulk of the remaining chapters.

- Chapter 2 - Planning Challenges and the Challenges of Planning

-

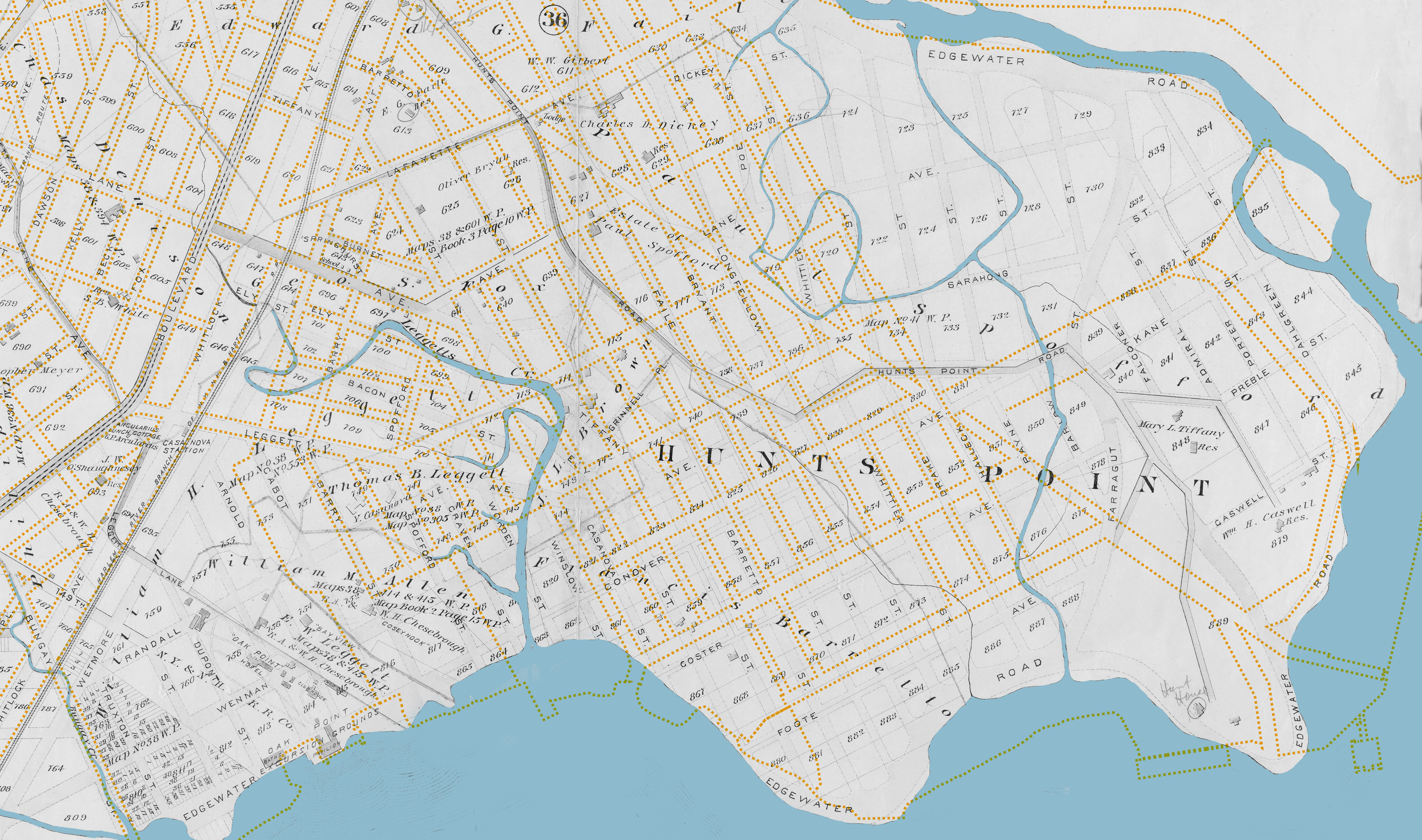

We would, however, fall into the same trap as traditional textbooks if we were to introduce these building blocks without context and, therefore, devote a whole chapter on two real-world planning situations (Roosevelt Island and Hunts Point, both in New York City). They follow a common workflow starting with a historic and geographic setting and a description of the people that live in or use the study area. This is followed by an analysis of the local needs and resources, which finally translate into planning challenges and opportunities. For the planning challenges, we follow the framework given in Chapter 2. Our case studies can be read by themselves as vignettes. Their main purpose, however, is to serve as a backdrop to the discussion of the other chapters, where we will make frequent references to the case studies. Throughout the book, we emphasize the need for a comprehensive and synthetic perspective; the methods described in chapters 4 and 5, for instance, should not be applied out of context.

- Chapter 3 - Case Studies

-

The first “methods” chapter discusses approaches that are related to the earliest stages of the planning process. As we stress the importance of communication, we start with the Delphi method as a precursor to e-democracy efforts (Rotondo 2012). Traditionally the domain of expert plan making and forecasting, the Delphi method can now be seen as bridging the gap between experts and non-experts. This naturally leads to a discussion of top-down vs. bottom-up approaches and the role of bias dealing with either community. While there still is a place for analog and face-toface techniques, contemporary planning takes place in a new media landscape and with a citizenry of variable digital competency (ICTA 2005). In this context, the bulk of our envisioning techniques deals with larger and often incoherent groups. In our attempt to incorporate as many different perspectives as possible, we reflect on citizen science, crowdsourcing, and participatory mapping. Individual perspectives can be captured through digital storytelling and photovoice, both of which can be used in framing the research question as well as plan implementation (Chapter 7).

- Chapter 4 - Planning Grand

-

The first “methods” chapter discusses approaches that are related to the earliest stages of the planning process. As we stress the importance of communication, we start with the Delphi method as a precursor to e-democracy efforts (Rotondo 2012). Traditionally the domain of expert plan making and forecasting, the Delphi method can now be seen as bridging the gap between experts and non-experts. This naturally leads to a discussion of top-down vs. bottom-up approaches and the role of bias dealing with either community. While there still is a place for analog and face-to- face techniques, contemporary planning takes place in a new media landscape and with a citizenry of variable digital competency (ICTA 2005). In this context, the bulk of our envisioning techniques deals with larger and often incoherent groups. In our attempt to incorporate as many different perspectives as possible, we reflect on citizen science, crowdsourcing, and participatory mapping. Individual perspectives can be captured through digital storytelling and photovoice, both of which can be used in framing the research question as well as plan implementation (Chapter 7).

- Chapter 5 - Placemaking: Why Everything Is Local

-

Our fifth chapter can be considered our “data and needs assessment” chapter. Data, in all its diversity and messiness helps us from making the mistake of relying completely on our instincts. Instincts can be good, but can sometimes lead us astray. We deal with the myriads of ways we can get hold of the data that underlies every rational planning process. We juxtapose traditional (though sometimes altered in their character by the surprising variety of provenance) outsider perspectives like demographic profiles with various community-based techniques such as behavior maps, participant observation, sensor, perceptional mapping, or modern survey techniques. Regardless of how all this data is generated, it then needs to be critically assessed to be used in scenarios or simulations. We outline the opportunities afforded by these techniques but also provide cautionary notes on their constraints and reflect on the role of planners in a world where technically skilled but non- professional citizens are confounding officials with their data wizardry.

- Chapter 6 - Civic Engagement

-

This chapter argues that contemporary planning has to go beyond public outreach or even public participation and introduced civic engagement as the third phase after advocacy planning and citizen participation (Holman et al. 2007, Healey et al. 2008). We propose four principles of civic engagement that serve as measures of successful community involvement and place a range of techniques into a matrix of stakeholder involvement. Many of the strategies presented here have been field tested over the past decade, working with a range of special populations. We summarize this chapter with reflections on the interplay of techniques and the need for planners to creatively and combine them as the situation demands.

Chapter 6 focuses exclusively on the complexities of civic engagement. The contemporary planning landscape is highly complex. Most planning projects or policies engage a range of state and non-state actors and it is useful to acknowledge that all projects are highly reliant on successful engagement with a variety of stakeholders. Civic engagement can influence a project or program’s success or failure – and in the 21st century, it is a truism to observe that good projects and ideas can sometimes be derailed because of poorly managed civic engagement processes (Malik & Wagle2002).

Civic engagement is simultaneously a philosophy, a core value, an approach, and a set of methods, and includes measurable indicators and outcomes (Hawkes 2001, Madera 2010, Gough 2015). It exemplifies the complexity of the planner’s role in society, regardless of the particular job title or function she performs. For this reason, we treat civic engagement as a stand-alone chapter because the various methods discussed in chapters 4 and 5 may have to be put through a civic engagement “test” in order to determine how these methods and approaches can and should be used within a planning process.

Note the use of the phrase “civic engagement” in this book, rather than commonly used terms such as public outreach, public involvement, or public participation. These terms are used interchangeably in mainstream planning discourse but they do not mean the same thing. In this book and chapter, the authors emphasize civic engagement — a term that connotes a genuine commitment to informed and reasoned deliberation and debate about a wide variety planning issues over an extended time period. Shifting the conversations from public involvement to civic engagement is one of the true lessons a successful planning practitioner must learn in order to be effective in his or her job. It is impossible to be a leader in the field without mastering the art and science of civic engagement.

- Chapter 7 - Implementation

-

We emphasized in Chapter 4 the importance of communication and revisit the topic now from a different perspective. People make decisions. Decisions are shaped by ideologies and political agendas. This is a point we make early in the book. However, in this penultimate chapter, we want to emphasize the role of policy in driving good implementation and securing it for future generations, in other words making it sustainable. Therefore, we will discuss the interplay between planning and policymaking here, focusing how to do identify and assess different policy options. Once identified, they have to be formally accepted through legislation, regulation, or larger structural societal transformations. In our media-driven age, this means that we have to pull out all stops to assure project-internal communication as well as getting the word out via web-based tools, meetups, hackathons, or engaging civic-minded people. We need to fund our plans, find allies, and, if necessary, create them by educating our clientele about modern planning practices and more generally how government works. Part of this not just the data fluency advocated for in chapters 4 and 5 but also to communicate with data to reach different audiences and maintain a sustainable planning environment, as highlighted particularly in the Roosevelt Island case study. Arguably, this reaches into the realm of senior planning management but it is never too early to learn about institutional constraints to turn them around into opportunities.

This chapter will allow planning students and practitioners to understand the differences between process-oriented policymaking, analysis-centric policymaking, and macro-scale policymaking. It discusses how to identify and assess different policies and their intended effects on different population groups (equity considerations) as well as how to avoid unintended consequences. Often planning students, especially those trained in the technical fields like engineering and architecture believe that their work ends when they present the technical studies and reports to their “bosses”. The bosses are often elected officials who have earned the right to represent the public, whereas the planners or practitioners are considered unelected decision-makers. However, the planners/practitioners may likely be the individuals who provide continuity for projects and programs that are multi-year investments from the public purse. Constantly undertaking research or planning studies that do not result in tangible outcomes is costly in more ways than the obvious – it has the potential to undermine the public’s trust in research.

- Chapter 8 - Epilogue

-

This chapter provides a chronological timeline of a typical planning process and creates a visual schema to link to different parts of the book. We practice what we preach, by creating an engaging visualization to succinctly tell a story about how to use the book and where to find the information they need. We realize that a book like this one is virtually outdated by the time it is published, which is why we will use the companion website allthingsplanning.org.